Contents

Chargebacks – What Agencies Need to Know Part 1

Chargebacks Overview

Card payment processing for government agencies has a lot of nuances. One of those nuances is that most government agencies do not pay for their card payment processing, but rather their constituents do through service or convenience fees. These fees are collected and paid by a payment processor who processes the card payments on behalf of the government agency and assesses their constituent a service or convenience fee.

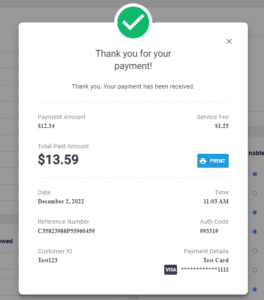

A payment processor will open a payment merchant account, which processes the constituent’s payment and deposits the money into the government agency’s bank account. The payment processor will also open a service or convenience fee merchant account, which deposits the service or convenience fee into the payment solutions processor’s bank account. The payment processor then uses the service or convenience fee to pay the card payment processing fees for both the payment and service or convenience fee merchant accounts. Because there are two card payment processing accounts, a constituent will see two separate card transactions appear on their credit or bank card statement.

One card payment will have a merchant descriptor that looks something like Government Agency ST, and the service or convenience fee will have a merchant descriptor of GovtAgencyST*Service Fee.

A key component of the two-transaction service or convenience fee is for the constituent to opt into the transaction by verbally agreeing or checking a box acknowledging they are paying the service or convenience fee to use their credit or debit card.

Mechanics of Chargebacks

A constituent has 120 days to chargeback a card payment on their statement. After reviewing their statement, a constituent will contact their credit or debit card issuer online or over the phone to chargeback the card payment. Because there are two card payments, a constituent can chargeback one or both. As soon as the constituent files a chargeback, the card issuer will likely issue the constituent a provisional credit for the card payment amount.

What Happens Next

When the constituent files a chargeback, the card payment amount is debited from a bank account on file with the payment processor. Typically, this means the funds will be taken from the payment solutions processors’ bank account.

At this point, the card payment the constituent made has been taken back from the payment solutions provider, but the government agency still has the funds. Since the government agency has already been deposited the card payment amount, the payment solutions processor will need to work with the government agency to debit the government agency’s bank account so that both entities’ bank accounts are whole.

The government agency will also need to reverse the payment that was recorded to reflect the constituent still has an unpaid amount. After adjustments for the chargeback have been made, it is as if the original payment had never been made.

Some payment solution processors charge a higher service or convenience fee to cover chargebacks that may occur. These payment processors absorb the chargeback amounts because they will charge enough additional fees to cover the chargebacks. Sometimes just the service or convenience fee will be charged back, but not the payment transaction.

Since the payment processor is paying the processing fees and relies on the fee transactions to cover those costs, they will typically ask the government agency to either help collect the service or convenience fee from the constituent or ask the government agency to refund the original payment and have the constituent start the payment process over again.

Two Charges an Agency Can See

Two charges a government agency might see are chargeback and retrieval fees. The government agency’s processor debits the payment solution processor’s bank account first. The payment solution processor then will debit the government agency’s bank account

Government agencies can treat chargeback and retrieval fees like an NSF (non-sufficient funds) fee on a paper check and pass it along to the constituent, so the government agency is not out any money. Retrievals are when the constituents issuing bank has to research a transaction because of a cardholders inquiry. Retrievals occur before chargebacks and sometimes can avoid chargebacks. However, there is a separate fee for a retrieval request.

After a constituent charges back a card payment, a government agency will receive a chargeback notice from their processor’s chargeback center informing them of the chargeback and asking for supporting documentation. Government agencies can work with the payment processing provider to provide documentation or accept the chargeback, reverse the transaction and ask the constituent to make payment via an alternative method.

The latter tends to involve less time and effort and be more effective than the time spent fighting chargebacks.

Efforts to fight chargebacks will require documentation to be submitted substantiating the charge, evidence to support the idea that the constituent initiated the payment, and proving the agency disclosed the terms and conditions to the cardholder at the time of the transaction.

Potentially including signage or screenshots of what the constituent would have seen at the time of the transaction. Many of these items can be time consuming and/or demonstrate.

The exact details of what will need to be provided will have to be determined based on the reason code that comes in with the chargeback. For example, if fraud is claimed, efforts would need to focus on the identity of the cardholder matching the identity of the constituent. If they don’t match, it will be an uphill battle. Alternatively, if the reason was the cardholder did not recognize the charges, the documentation efforts would need to focus on the charges owed and what the cardholder would have seen at the time of the transaction.

A Word About EMV

EMV is a security technology and payment processing standard developed By Europay, Mastercard, and VISA to reduce in-person credit card fraud. EMV-compliant payment cards have a chip embedded and produce a single-use code when inserted into EMV compatible reader or POS terminal. So, when a customer inserts or dips the payment card, the POS terminal authenticates the card with the card issuer’s system, and a single-use transaction code is confirmed.

A wrinkle is the EMV Liability Shift, which went into effect in October 2015. The liability shift transferred fraud liability from the card issuer to the entity with the lessor technology with card-present transactions, whether that is the government agency, card issuer, or the acquiring bank.

Suppose the government agency does not have an EMV card payment processing device, and their constituent pays with their EMV card, which turns out to be fraud. It is the government agency that is responsible for the fraud. In other scenarios, the acquiring bank could be responsible for the fraud. If the government agency has an EMV card payment processing device and the card used during the card payment is EMV, then the card issuer is still responsible for the fraudulent card payment.

One of the many nuances to government payment processing is that government agencies have their own recourse via various methods. So there is little incentive for a constituent to chargeback a payment. Whereas if that same constituent charged back a card payment from a local business, the only recourse the business has is to accept or fight the chargeback. Moreover, merchants only win 21% of the chargebacks when they submit supporting documentation.

After the government agency submits its supporting documentation, the issuing bank will decide who won the chargeback. If the issuing bank finds in favor of the constituent like they do 79% of the time, it creates a hardship for the government agency. It is important to emphasize that chargebacks in government payments are rare. Still, the issue the constituent causes with a chargeback is that card payment is public money used to fund the local government.

Why Do Chargebacks Happen?

Top Three Chargeback Categories

According to Chargebacks 911 (CB911) there are dozens of chargeback reasons codes. These different categories are used to classify chargebacks. These categories vary slightly based on the

card brand but can generally be divided into three categories: Criminal Fraud, Friendly Fraud, and Merchant Error.

The cardholder’s bank reviews each case and picks the category (or reason) that seems to be the best fit for the chargeback. CB911 found that friendly fraud accounts for 60-80% of chargebacks,

which most of the chargebacks in government payments are.

The second most common chargeback reason code is merchant error, which accounts for 20-40%. Finally, criminal fraud only accounts for 1-10% of chargebacks. If a service or convenience fee is small, say $1.50, the card payment is often charged back. Why? Fraudsters will run the card for a small amount to see if the cardholder will notice the fraudulent charge before using the card for a more significant purchase.

Other Friendly Fraud Reasons

Here are some other reasons why a constituent might initiate a chargeback:

Merchant Descriptor

One is the billing or merchant descriptor, aka retail, statement, or merchant descriptor – the text and number series that identifies the party that received payment. The cardholder uses the merchant descriptor to identify to whom and why they made a payment. If the constituent’s card statement merchant descriptor is unclear, the constituent will probably file a chargeback.

Typically, the merchant descriptor was set when the government agency opened the merchant account, and if needed, it can be changed by contacting the government agency’s payment processor. A government agency’s payment processor can do their part by setting up the service or convenience fee merchant account with an accurate retail descriptor to display on the constituents payment statement.

Forgot

Government payment chargebacks also occur when a constituent does not remember agreeing to pay the service or convenience fee. This reason is especially valid for online payments where constituents blindly check boxes to complete the transaction.

Two Transaction

The constituent might not realize when they read their statement that their payment comes across in two transactions, one transaction for the government agency’s invoice/bill amount and one for the service or convenience fee. If the service or convenience fee descriptor is different or unclear from the merchant descriptor used for the invoice/bill they paid, it only adds to their confusion.

In our next post, we examine in more detail why chargebacks happen and how to prevent them.